Contributing Guest Writer, Nydia Simone @Blactina

The soul of Tango was Black all along. The untold story behind Argentina's iconic Tango dance will challenge everything you thought you knew.

It was 1887, the room was filled with cigar smoke that engulfs couples with their sharp pauses and hip flips…closer than close their embrace defies the rule of law. Afro-Argentine dockworkers and domestics, sailors and Italian immigrants fill the dimly lit room enjoying their fleeting leisure. The door of Café La Marina bursts open, Police flood the room, barking accusations of “immoral dancing!” and “illegal gambling!” as the reason for the raid. Patrons scatter; drums fall to the floor. Tango’s cradle was forbidden. It was Black. And it was breathtaking.

Enslaved Africans at the Río de la Plata: Birth of a Beat

The origins of Tango lie in the resilience of enslaved Africans brought to the Río de la Plata formed along southeastern coastline of South America. Enslaved labor included domestic servants, artisans, cattle herders and port laborers, forced to build cities, process beef in hellish saladeros (salting plants), and load ships under the whip of colonial profit and dehumanization. Even after being forced to do dangerous jobs, sexual exploitation was routine. By the 1800s, nearly half of Buenos Aires’ population was of African descent. They carried rhythms like the Candombe, a drum-driven Uruguayan tradition, and the Milonga, a rapid-step dance of courtship and competition. The word "tango" likely derives from the Kikongo (Bantu) term "ntangu" (pronounced n-TAHN-goo), which means "time," "moment," or "sun." In the Río de la Plata region, enslaved Africans referred to their drum circles as "tangós". This term may have merged Bantu ntangu (time/meeting) with Spanish influences. These gatherings were often repressed by colonial authorities.

Candombe, Milonga & the 3‑3‑2 Clave: Tango’s Rhythmic DNA

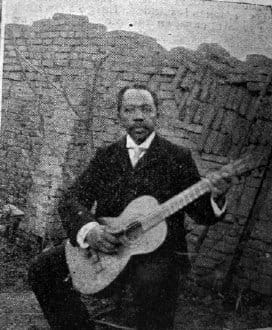

Beyond its hypnotic movements, tango served as a powerful medium for storytelling, giving voice to the silenced. Enslaved Africans encoded their struggles into its rhythms like the *3-3- 2* clave of Candombe, which echoed West African polyrhythms and defiance. Black musicians such as Higinio Cazón infused tango with African melodic phrasing, blending Spanish guitar with Bantu call-and-response in early milongas. His compositions preserved Kongo Angolan tresillo rhythms under the guise of folk music.

Black Payadores and Dockworkers: The Real Storytellers

Meanwhile, as Argentina's government waged war on gauchos (cowboys) tango became their lament. The legendary Black payador (folk singer) Gabino Ezeiza immortalized their plight in songs like "Saludo a Paysandú" (1894), where African-derived rhythms illustrate tales of displacement and resilience. Through its melodies and lyrics, tango wove together the struggles of enslaved Africans, exiled gauchos, and impoverished immigrants which transform oppression into art.

Whitening Campaigns & Census Erasure (1860‑1940)

Argentina’s government promoted Mestizaje and Mejorar La Raza extensively, a whitening movement that sought to exterminate Indigenous and African existence in favor of a mixed race that mirrored white European ideals. To fashion a “white nation,” Blackness was through wars like the Paraguayan War, where Black soldiers were forced to fight on the front lines killing many. Forced assimilation or invisibility by removing Black from the census in 1888 and heavily promoting European immigration.

According to scholar Erika Denise Edwards “Afroargentinos actively participated in Argentina’s wars for territorial expansion and suffered from high casualty rates. One of the worst losses suffered by the country during the war for independence occurred in 1815 at the battle of Sipe Sipe, where 1,000 Afroargentinos were killed, captured, or wounded, while 20 Spaniards were killed and 300 were wounded. A 1905 statement in the newspaper Caras y Caretas triumphantly declared the supposed disappearance of the Black population, describing how the “African tree” now produced “white flowers.” By 1940, Argentina’s Black population had plummeted from 30% to under 1%. This “whitening” peaked post-WWII, when Argentina sheltered Nazis and provided lucrative immigration benefits (free land, no taxes) to European immigrants who blended into a society eager to forget its African and Indigenous roots.

From Brothels to Ballrooms: How Europe Fell for a “Forbidden” Dance

By the 1890s, tango seeped into Buenos Aires’ red-light districts, where white immigrant men learned its steps from Afro-Argentine dancers. As tango gained popularity, its Black pioneers were gradually erased from history. Casimiro Alcorta, born a slave and freed as a child, is considered one of the founding figures of tango. He composed early pieces like 'Entrada Prohibida' ('Forbidden Entry'), yet his name and contributions were largely forgotten or attributed to white musicians. Other pioneers include Rosendo Mendizábal, a mixed-race pianist, who wrote “El Entrerriano” (1897), one of the first published tangos, but died in poverty.

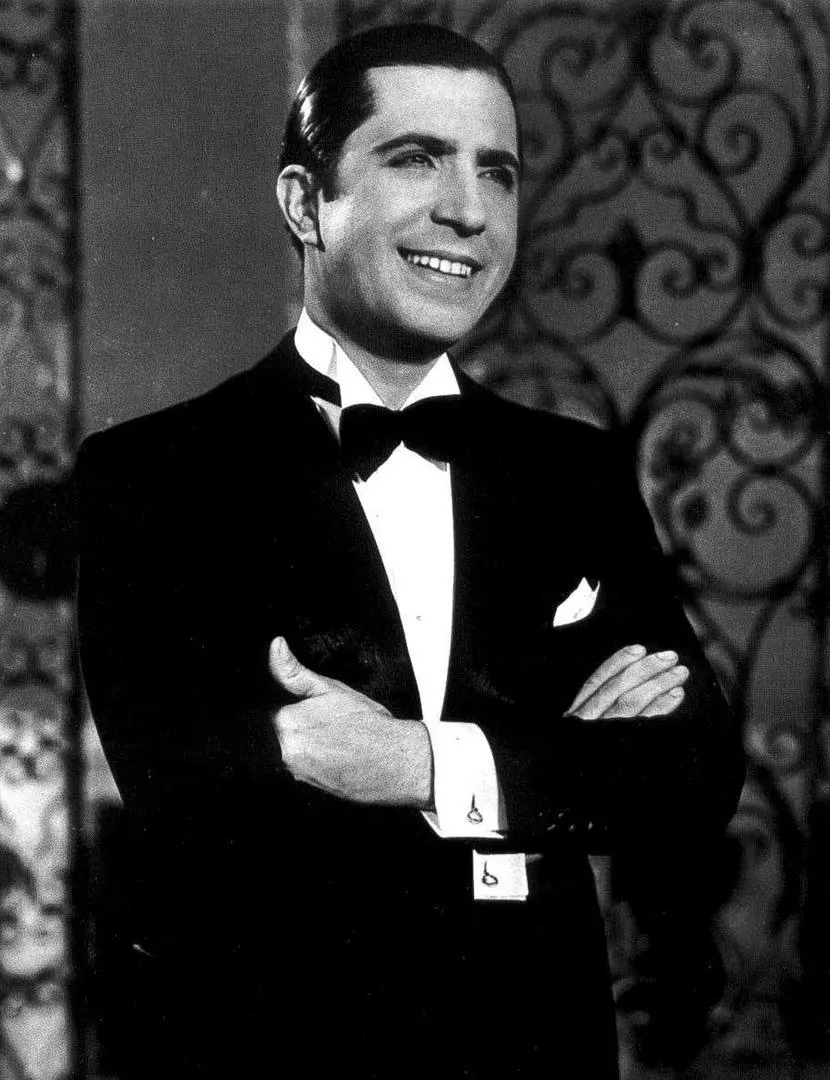

As with many Black cultural inventions, what one society tries to suppress, another embraces as exciting and new. When Paris caught wind of tango in 1913 the white elite flocked to it. Carlos Gardel, a white artist with controversial French roots copied payadores (folk singers) like Gabino Ezeiza and virtuoso dancer "El Negro" Sinforoso used their genius to catapult himself to fame. But while some were enchanted by this scandalous new art form, others sought to repress it. Pope Pius X condemned it and Kaiser Wilhelm, the last emperor of the German empire forbade his officers from dancing it. By 1914, cities across the United States, from Boston and New York City to as far as Utah declared tango a moral threat. Critics claimed the dance’s intimate embrace “endangered youth” and could even destroy marriages.

The Battle Over Lunfardo Lyrics and Argentina's Law 11.709

In 1921, Argentina’s Law 11.709 criminalized lunfardo in tango lyrics, branding it “vulgar” and “un-Argentine.” Lunfardo blended Italian dialects (from Genoese and Neapolitan immigrants), African, French, and Spanish terms. Words were often flipped, vesre: “revés” backwards and tango becoming gotán. Authorities feared its power to unite the working class and preserve Black and immigrant identities.

Francisco Canarozzo later Francisco Canaro of Italian descendants was born in Uruguay and became the first millionaire of Tango in 1928. He is credited with making it palatable for white conservative audiences. He played a crucial role in transforming tango into a mass-market product, taking it from the margins into ballrooms, concert halls, and radio stations. While many white musicians performed in upscale ballrooms, most Black musicians were confined to street corners and local taverns.

After the 1930 coup led by José Félix Uriburu, tango once banned as the "devil’s dance" for its Afro-Argentine sensuality and working-class connection, underwent a sanitization. Under Argentina’s military-backed elite, tango was stripped of its Black, Indigenous, and immigrant soul, then repackaged as a refined "white, Catholic" art form. Gone were the sweat soaked candombe rhythms of Afro-Argentine dockworkers and the unruly camaraderie of Italian laborers in La Boca’s dwellings. In their place emerged a whitened tango, its origins sterilized for high-society ballrooms. The same government that had once raided dance halls for "immoral conduct" now celebrated tango as a national treasure only after ensuring its rebellious roots were erased. This was more than censorship, it was cultural surgery.

By severing tango from its Black creators and working-class immigrant innovators, Argentina’s ruling class reforged it into a symbol of European purity. However, the rhythm never disappeared. The African roots of Tango will always survive in the margins and is now resurging with efforts to reclaim its Black, African origins and honor its legacy.

Sources:

• Moya, José. "Cousins and Strangers: Spanish Immigrants in Buenos Aires, 1850– 1930." (1998)

• *Andrews, George. "The Afro-Argentines of Buenos Aires, 1800–1900."* (1980) • Archivo General de la Nación: Immigration Laws (1875–1914)

• Ezeiza's "Saludo": Field recordings at Museo Nacional del Tango (Buenos Aires). • George Reid Andrews, "Afro-Latin America" (2004)

• Jorge Miguel Ford, "El Payador Gabino Ezeiza" (1998)

• Álvaro Montenegro, "Huellas del Bantú en el Tango" (2010)

• Matthew B. Karush: Culture of Class: Radio and Cinema in the Making of a Divided Argentina (2012)

• “El Origen Negro Del Tango.” www.cultura.gob.ar, www.cultura.gob.ar/el-origen negro-del-tango_6929/.