Bigger Than Life

Frida Kahlo’s art was always revealing the dramatic events in her life, and the strong feelings they produced within her: the chronic pain and health problems produced by the accident she suffered at 18, the often counterproductive efforts to ease them, and the strong but complicated relationship she had with her husband and fellow artist, Diego Rivera, which was constantly in the public eye and intertwining with their artistic processes.

But to focus only on these aspects is to miss out on the subjects and explorations that her art depicted: Mexican folk culture, surrealism and magic realism, politics, and questions on gender and class. Few other art icons were so defiant and vulnerable, political and personal like Frida, and her continuous influence to other Latina artists and iconic presence to this day only proves it.

Pop culture and the media have produced uncountable recounts and depictions of her life, from Latino children's books about her artistic contributions to the 2002 Frida Kahlo movie and 2018 Frida Barbie doll model which have delved into the controversy she sparked at her time, her most iconic looks, and even how she died. The most recent discovery came from Mexican officials possibly finding a voice recording of Frida. However, we’ll be focusing solely on her work, which continues to be the best recount of the circumstances she went through, and of her strength and unique vision.

Six Fundamental Frida Kahlo Paintings

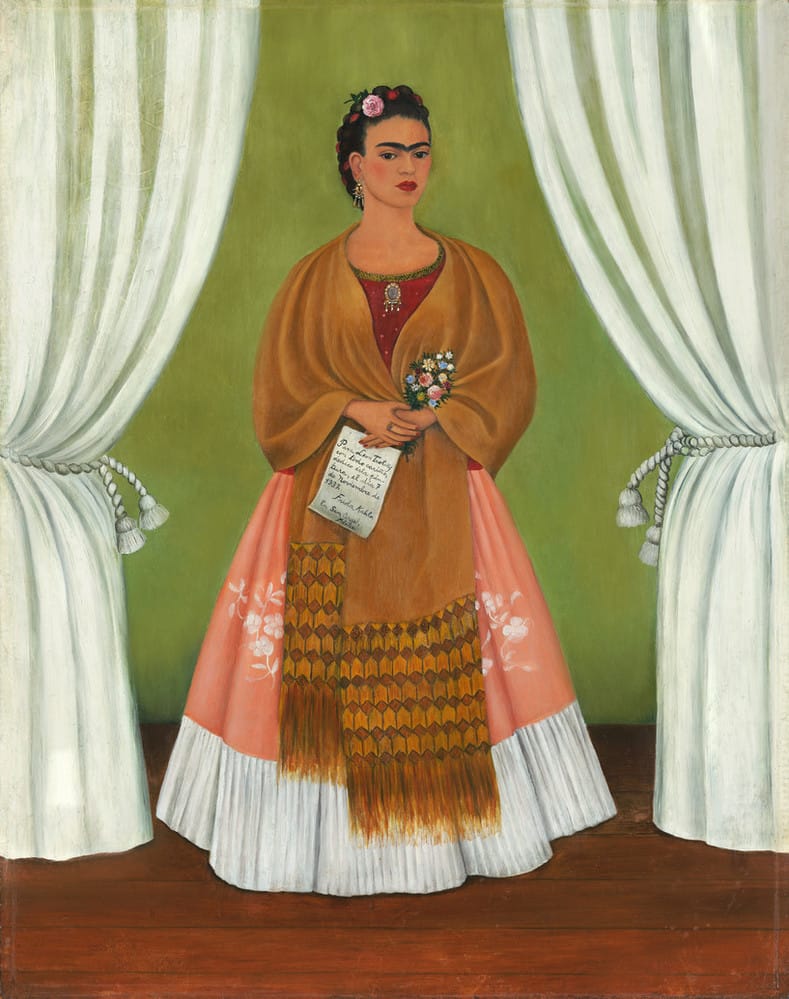

Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky (Autorretrato dedicado a León Trotsky, 1937)

At the most basic level, this painting commemorates the affair Frida had with Leon Trotsky, who took up residence (along with his second wife, Natalia Sedova) in Frida’s Blue House (Casa Azul), in 1937. But it’s also a testimony of Frida’s commitment to his political views, and her first step towards showing her own views around Marxism and Communism—she was already portrayed in Diego’s 1928 In the Arsenal (En el arsenal), handing out weapons to revolutionary soldiers. In 1954 she produced Marxism Will Give Health to the Sick (El Marxismo dará salud a los enfermos), the unfinished Portrait of Stalin, and Self-Portrait with Stalin (Autorretrato con Stalin). Given how things ended between Stalin and Trotsky (the former successfully got the latter killed), the intertwining of Frida’s life and political views becomes an unmeasurable factor.

The Two Fridas (Las dos Fridas, 1939)

Is the Frida on the left the representation of Frida’s European heritage and the other one the symbol of the Mexican legacy? Is the Frida on the right, with her heart intact, the one Diego loved, and the one on the left, with her heart ripped open, the one Diego rejected? Or is the painting, as she said in her diary, just the memory of a childhood imaginary friend?

Some things about this work are certain: it was made during Frida’s divorce from Diego, which surely contributed to the dual image of the painting, the cloudy background, and its interpretations, and it was inevitably linked to surrealism, being exhibited for the first time on the “International Exhibition of Surrealism,” in Mexico City.

Although she didn’t consider herself a surrealist, her works often reminisced the style of Hiëronymus Bosch and Francisco Goya, who influenced the surrealist movement, and the Mexican Museum of Modern Art, where The Two Fridas are exhibited, considers the sky in the background to be inspired by El Greco, who also led some of the artistic innovations that surrealism would introduce.

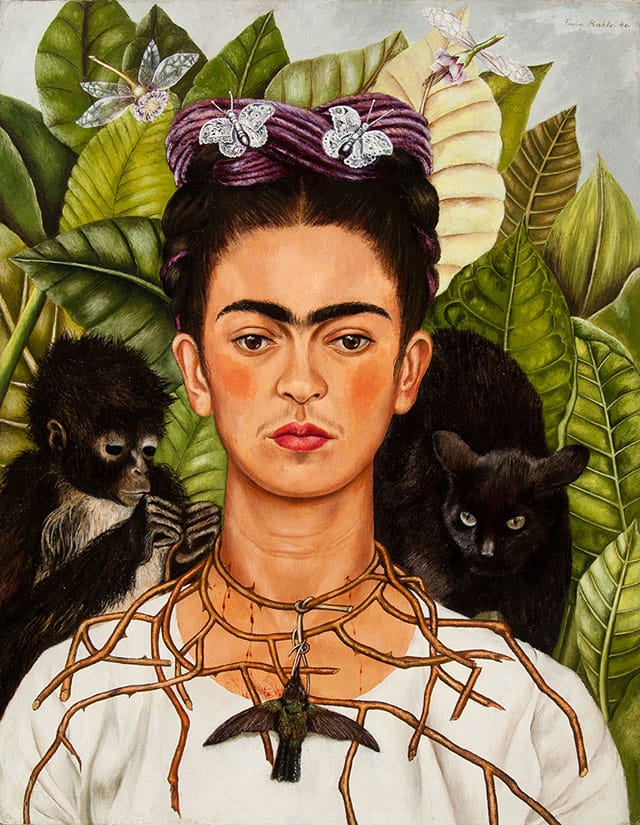

Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (Autorretrato con collar de espinas y colibrí, 1940)

The necklace of thorns, which causes Frida’s neck to bleed, and her solemn expression, while she endures the pain, give a clear message—this work is, first and foremost, a statement about her resilience. And despite its rather small size (about 24 in × 18 in), it became one of her most iconic self-portraits thanks to the strong presence and symbolism of the creatures around her: the monkey holding the necklace, the hummingbird hanging from a thorn, the cat, the dragonflies, the butterflies.

This is another work from the period of Frida’s divorce from Diego (not long before they remarried), and it was purchased by photographer Nickolas Muray, with whom Frida had an affair that ended in 1939. It was in Muray’s New York apartment until 1965, as the backdrop of his daily life, but also as a witness of his social life, which included gatherings with personalities such as dancer and artist Rosa Rolanda, artist (and Rolanda’s husband) Miguel Covarrubias, and actress and fashion icon Anna May Wong.

Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (Autorretrato con pelo corto, 1940)

Holding on or enduring pain wasn’t everything for Frida at the time of her divorce: this painting was a portrayal of autonomy, of moving forward, and the androgynous persona she embodies may even be a challenge to the gender standard. Many aspects of the previous paintings are cut off (literally or metaphorically) in this one: she’s holding the scissors with which she cut her hair, the Tehuana dress gives place to a man’s suit, and animals are displaced by the lyrics, in Spanish, of a corrido song of the time: “See, if I loved you, it was because of your hair, now that you are bald, I don’t love you anymore.”

The transformations showcased in this painting were still a reaction to her divorce but also anticipated how her work would be seen in the future: although unavoidably connected with Diego, it would stand on its own.

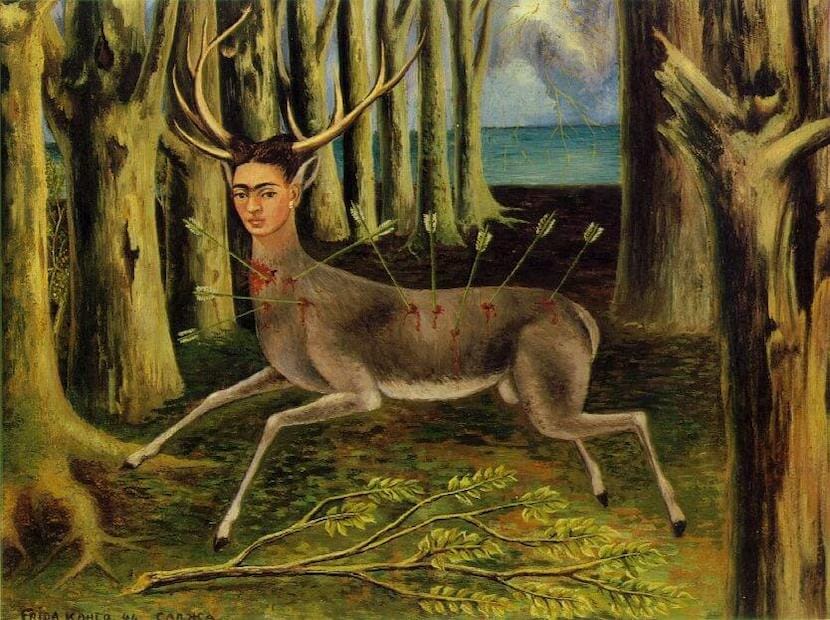

The Wounded Deer (El venado herido, 1946)

Around the complex—and failed—surgery she went through in New York in 1945, the paintings of this period expose the despair for her declining health: The Broken Column (La columna rota, 1944), Without Hope (Sin esperanza, 1945), Tree of Hope, Remain Strong (Árbol de la esperanza, mantente firme, 1946), and The Wounded Deer are some examples of this somber period.

In this work she presents the same stoic look on her face (her only human feature, having the body of a deer), but signs of the imminence of death seem to be everywhere: nine arrows are making her body bleed, fallen leaves lie between her legs, the trees’ canopies can’t be seen, and the word carma (“karma”) appears next to her signature.

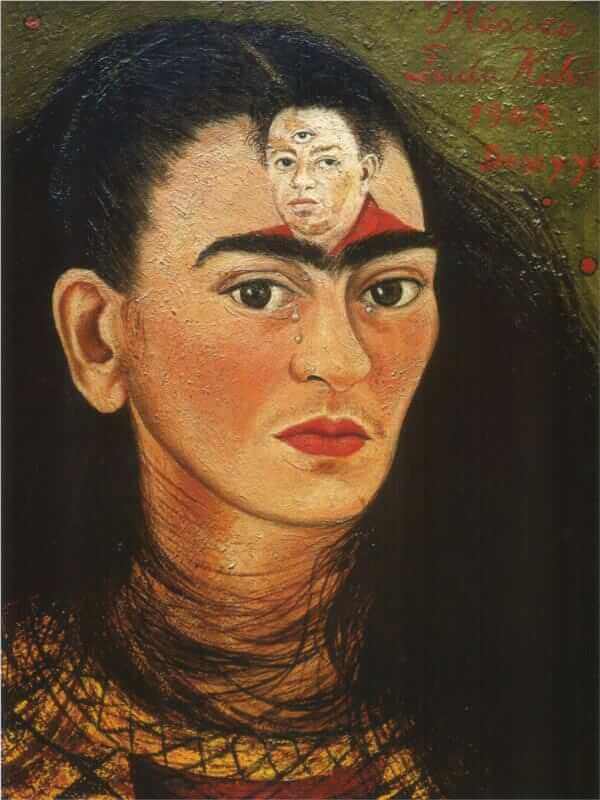

Diego and I (Diego y yo, 1949)

Beyond any vow or faith they would be together forever, it seems as if Frida and Diego’s paths were set to cross in many ways: when auctioned at Sotheby’s in 2021, this painting was sold for $34.9 million, becoming the most expensive Latin American work of art to be sold at an auction. And which painting held that record until then? Diego’s Los rivales.

This self-portrait was made around one of the most tumultuous points in their always troubled relationship: Diego’s affair with Mexican actress Maria Félix, which was highly covered by the media. It was also the time when Diego was quoted saying “I adore Frida, but I think my presence is very bad for her health.” The painting seems to underline his words, with her tearful look and the central place that he takes in her mind.

A Frida Kahlo Museum That Feels Like Home, and One Key Exhibition

The Casa Azul in Mexico City, the place where Frida was born, lived with Diego, and died, was turned into a museum in 1958, and since hosts a collection of Frida and Diego’s personal items and paintings, as well as Mexican and pre-Hispanic artifacts and works of art. It’s not only an amazing peek into their everyday lives and their most significant objects (like Frida’s four-poster bed with the mirror, or the easel she received from Nelson Rockefeller), but also into the ambience that inspired their art.

Meanwhile, Throckmorton Fine Art Gallery in New York is hosting “Frida Kahlo, Forever Yours…,” a selection of nearly 50 rare photographs that includes early portraits taken by her relatives and some iconic shots by Nickolas Muray. It’s a very significant tour through the intimate and public corners of her life, showing her in relaxing and spontaneous moments but also underlining her colossal and captivating presence.