I come from places where enduring inequalities is the norm. I’ve seen my mother come home exhausted after a long day of work struggling to keep her body from collapsing. I’ve seen her massage her arthritis affected hands describing the way her supervisors screamed “faster! faster!” to her and the rest of her coworkers, most of whom were undocumented Mexican women. She gave tireless physical labor only to receive a meager paycheck barely big enough to get us through the next few days. I grew up sharing a tiny bedroom with my brother, sister, mother, and father. My mother continues to endure worker exploitation because the job market is scarce for people who don’t speak English and cannot afford a car. She drew power from her experiences to give me the most potent words of advice: “Mija, tu estudia para que no sufras como yo,” meaning, “my daughter, get an education so that you won’t have to suffer like me.”

“I’ve expanded into places that my ancestors couldn’t.”

These magical words of wisdom were passed down to my mother from my campesino grandpa. My grandpa dreamed that my mother would get an education so that she wouldn’t have to suffer as much as he did. He aspired for her to become a secretary. His eyes glistened as he pictured her in business attire working as a secretary; a job he considered was for important people. My mother was an outstanding student, who won talent shows, and excelled in her academics but her dream of getting an education was deferred due to poverty. At the age of 12 my mother said goodbye to her school friends in tears and began working because her parents couldn’t afford to feed her and her siblings. She’s told me this story countless amount of times and I still see the melancholy in her eyes every time she remembers it. Through these stories and through witnessing her arduous physical labor I began to understand that we live in a society that doesn’t value the labor of people of color who don’t posses a formal education. It was at this point in which I perceived formal education to not only be an escape out of poverty but a necessary tool for survival. I felt a mix of rage and helpless unrest so I engaged in a disruptive act against this system of inequality and oppression: I pursued my education.

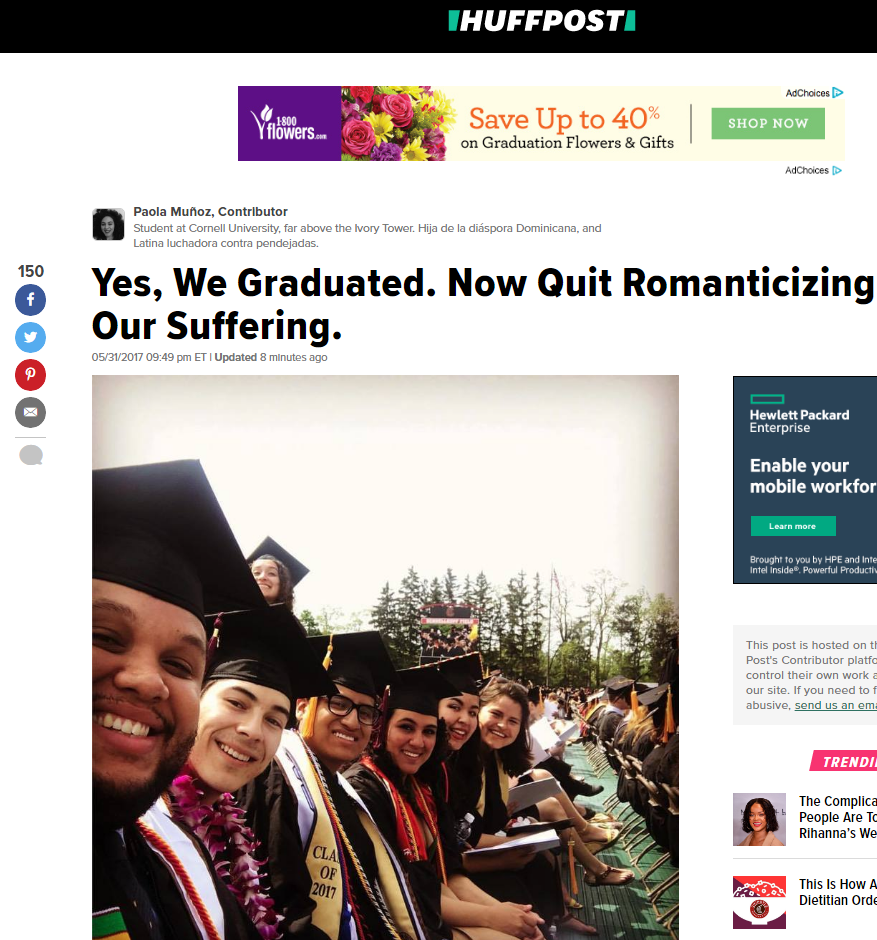

Image blurred to protect undocumented identities.

I became the first in my family to go to college even though I come from an ethnic community that has been systematically denied access to higher education. I moved nine hours away from home even though I come from a cultural practice in which women aren’t supposed to leave home unless they are going to marry a man. However, my mother always advised me to get a career so that I would not have to depend on any man. Pursuing a higher education was an act of rebellion against the machista tradition that said a woman’s place is at home with her husband. When my parents dropped me off in college they did so with tears in their eyes, wary of leaving their eldest daughter in a foreign place by herself. However, they understood my decision to leave because as immigrants who were once undocumented they too left their homes in search of a better life. I ventured on this journey with the same magical message that was passed down to me from my working class immigrant lineage: “Mija tu estudia para que no sufras como yo.” Pursuing a higher education was an act of leadership as I trail blazed along unknown territories and demonstrated to my community that another option is possible.

The day of my college graduation was one of the most rewarding days of my life. Seeing the triumphant look of pride on my mother’s teary face when I walked the stage felt like reaching milk and honey after pushing through a torturous desert. It felt like I was avenging my ancestors. The pressure first generation children of immigrants feel to prove to our parents that their sacrifices were indeed worth it can be awfully beautiful and produce outstanding results. We inherit a divine agency that can transform deprivation into possibility. She is a reflection of many low-income immigrant parents who selflessly pave the way for the next generations to pursue what they did not have the opportunity to achieve. I stand on the shoulders of powerful and resilient people who worked for me to be here.

To me, like many first generation low-income people of color, attaining a Bachelor’s degree represents much more than the closure of a chapter. It is a way to honor the sacrifices of our parents who crossed deserts and defied borders for better opportunities. Those parents who did not have the opportunity to get an education yet when raising their children instilled education as one of the highest values. It is overcoming the obstacles of a failed public education system, a society that criminalizes melanin-blessed skin, and a poverty that tries to crush our dreams. Graduating from college is a reminder that I am a smart, rebellious, brown, womxn thriving in a capitalist-white-supremacist-hetero-patriarchal society that is trying to crush me. The fact that I have come this far is, no doubt, a miracle. I’ve expanded into places that my ancestors couldn’t. I did not have the privilege of a selfish education and came with an understanding that this education was not just for me. My education is an act of resistance and this degree a tool to uplift my community. However, the most valuable and transformational education I have ever received has been the one of my middle school educated mother who taught me that selfless love and persistence can move mountains.

I am the explosion of her dream deferred. Caution: Educated Womxn of Color

READ: Romantizing Our Suffering… a piece written in solidarity by Paola Munoz

Rocio Z., our essay contributor is a smart and rebellious brown womxn who cherishes education. She is committed to uplifting her community and determined to thrive in a world where she was never meant to survive.