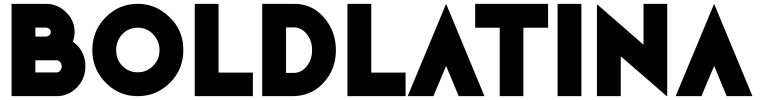

The Amazon rainforest of South America have faced a significant number of wildfires, leaving this ecosystem in ashes, with hundreds of thousands of hectares destroyed and exotic and rare animals dead, while a cloud of smoke travel across the continent and deteriorates the quality of the air. It’s safe to say we are nearing a ‘tipping point’.

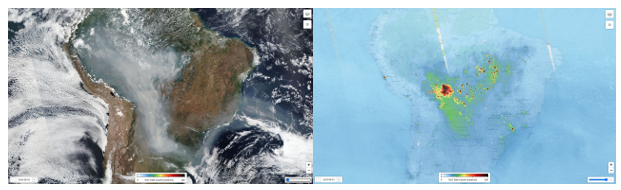

The dry season (August through September) has led to some of the largest and highest wildfires reported in the past decade, surpassing the record set in 2007 when 345,322 fire hotspots were registered, according to Brazil's National Institute for Space Research (INPE). The agency also reported that 346,112 fire hotspots have been recorded this year across the 13 countries that make up South America. Both ‘dry season’ and ‘man-made’ have contributed to this record-breaking season. The European Atmospheric Monitoring Service (Copernicus) reported that estimated carbon emissions increased in the last quarter due to wildfires, after remaining steady on average from 2003 to 2023. The most affected countries are Brazil and Bolivia. Brazil, the South American giant, has produced approximately 180 megatons of carbon so far, with nearly 60 megatons generated in September. Meanwhile, Bolivia, the ‘Andean jewel', reported an increase above average FRP values from July to September. In just the last month, emissions were recorded at approximately 30 megatons, with an expectation to close the year at around 80 megatons.

The above is the science, let’s get into the devastating impact.

Rising Temperatures and Deforestation Drive Devastating Wildfires in Bolivia

The last week of September 2024, the Bolivian government declared a "national disaster" under an emergency decree, seeking international aid to "protect natural resources and biodiversity for future generations." The Santa Cruz de la Sierra government, one of the hardest-hit regions, reported that more than 7 million hectares have been devastated by fire so far this year. The National Meteorology and Hydrology Service (SENAMHI) announced a forecast for a cold front with rain and thunderstorms in eastern Bolivia. While the impact of these ‘cloud seeded’ rains remains to be seen, they are expected to help combat the fires still ravaging the rainforests unfortunately, a ‘band aid’ solution.

As a result of the ongoing fires, the air quality index (AQI) was reported at 393 on Oct. 6, causing respiratory complications such as asthma and pneumonia for hundreds of local people. Scientists use a scale of 0 to 500 to measure air quality, with 0 to 50 being "good." Air quality between 50 and 150 may pose risks for individuals with respiratory or skin conditions, while levels above 151 are considered "unhealthy" for everyone.

Official government data reports that 11,747 families have been affected by the wildfires. The report also mentions that the recovery of ecosystems devastated by the fires could take up to 10 years. Jorge Vargas Roca, mayor of San Rafael, a municipal district in Bolivia, expressed his frustration at a local ceremony, noting that thousands of animals, including jaguars, were trapped by the flames.

Bolivian Government Takes Action to Curb Fires

As a measure, the government of Luis Arce Catacora has suspended all burning authorizations and has also prohibited the issuance of new concessions. These authorizations are part of a set of controversial laws and decrees approved during the government of Evo Morales (2006-2019), which promoted the expansion of the agricultural and livestock frontier in the Santa Cruz region. During his administration, the agricultural sector, also known as "agribusiness," grew significantly, accounting for an average of 10.6 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (2006-2019). In fact, according to an analysis of agricultural policies in Bolivia prepared since 2017, this sector has experienced a growth of 6.6 percent, encouraging exports. Furthermore, in 2019, it employed 26.1 percent of the economically active population, increasing the migration of citizens who settled in the fertile lands of Santa Cruz to cultivate the land.

However, there seems to be 'growth at all costs' consequences and that consequence is the continued damage of the Amazon rainforest and surrounding Bolivian and Brazilian urban and indigenous communities. The Bolivian local and national community are responding with fundraising and awareness efforts by social media influencers and small business owners, who are offering products or sales donated to fire fighting initatives .

Amazon Region Indigenous Communities Lead the Fight Against Wildfires

From the beginning of 2024 through September 8, Brazil recorded approximately 160,000 wildfires. These occurred throughout the country, from the Amazon to the Pantanal, one of the largest freshwater wetland ecosystems in the world. To put the distance between these two points in perspective, it would span approximately 1,500 to 2,000 kilometers if crossed in a straight line.

The intense fires have disrupted the "flying rivers," a phenomenon originating in the Amazon where water released by millions of trees travels through the air across the continent, humidifying the soil, irrigating crops, and feeding rivers and lakes. Now, this current has transformed into a massive cloud of smoke, making São Paulo one of the most polluted cities, albeit for just a few minutes. According to iQair, as of October 9, São Paulo ranked 13th on the list of the world's most polluted cities, with the number one position held by the most contaminated city.

The consequences of the fires can affect future generations. When flames reach trees with thin bark, they emit more carbon dioxide than they store for the next 10 years. Additionally, the fire weakens the canopy, which is formed by leaves, branches, and upper vegetation. As the canopy weakens, it absorbs more radiation, increasing the risk of wildfires, according to Ane Alencar, scientific director of the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM).

Many of the fires are human-caused and occur in Indigenous territories, where communities have been severely impacted by climate change. In the state of Mato Grosso, in western Brazil, flames have affected 41 of the 86 Indigenous lands, which encompass the Amazon, Cerrado, and Pantanal biomes. A total of 80 cities and more than half of the state have been impacted by the fires. High temperatures, low humidity, and strong winds have contributed to the rapid spread of the flames.

In response, the Guató Indigenous community, known as the "people of the waters," trained 24 of its members to form the first firefighting brigade in their territory. These individuals now make up the first volunteer brigade of the Guató Indigenous Land in northern Mato Grosso, home to around 200 people.

"The training was a community request because, in recent years, they have been isolated by the increasingly intense fires in the Pantanal, and they feared the flames would reach their territory," Elvis Terena from the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (Funai) explained to AFP.

Jorcimari Picolomini, a teacher at the Toghopanãa Indigenous school, noted that while there have been no fires in her village, there are nearby hotspots, so they must remain alert. Picolomini is one of seven women trained to act before the fire spreads.

Given the imminent dangers, training and equipping vulnerable communities provide time until firefighting brigades can take over. The Guató received personal protective equipment and tools to combat the flames.

Learn more about Latina Activists and Environmentalists we must honor.